The need to address the climate change crisis has led many countries like Nigeria to develop an Energy Transition Plan. The federal government launched the Nigeria Energy Transition Plan (the ‘ETP’) in 2022, a home-grown, data-backed, multipronged strategy designed to tackle energy poverty and the climate change crisis. The ETP aims to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2060 in 5 key sectors: Power, Oil and Gas, Industry, Cooking, and Transportation.

The net-zero pathway of the ETP proposes to tackle environmental issues like gas flaring, the use of traditional firewood, kerosene and charcoal, and the use of diesel and petrol generators. Furthermore, the ETP aims to tackle social problems like long-term job loss due to the reduced global fossil-fuel demand, eradicate poverty by increasing the standard of living of about 100 million Nigerians and create jobs.

The ETP outlines significant social and environmental impacts. However, there are underlying concerns about achieving the goals of the ETP, which this article addresses below.

Analysing the Impacts of the ETP

There is a need to address the gaps and challenges to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Firstly, the transition from fossil fuels leads to massive job losses in the oil and gas sector. The ETP aims to create up to 340,000 new jobs by 2030 and 840,000 by 2060. However, critics have questioned the feasibility of the ETP’s targets for job creation. One major obstacle to this goal is the lack of skilled workers in the renewable energy sector. The 2021 Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) report noted that a lack of skilled workers in the sector could impact employment in the oil and gas sector in the future. For example, one of the primary sources for job creation in the renewable sector is installing and maintaining a renewable energy system; this includes solar panel installations, wind turbine maintenance and hydroelectric plant operation. A significant gap exists in skilled workers such as engineers and technicians needed for these tasks. As a result, most of Nigeria’s renewables are imported because only a few companies manufacture and install renewable energy systems. Thus, investing in education, training, and skill development programs for the renewable workforce is essential to unlock the full job creation potential within the ETP.

Secondly, the impact on communities dependent on the fossil fuel industry can be damaging without adequate support and transition programs. The decline of the fossil fuel industry can also lead to economic decline in communities dependent on it, exacerbating the human development indices. A notable example is Appalachia, a region in the eastern United States known for its historical dependence on coal mining. The decline in coal production severely impacted the local businesses, mostly coal-related, the region’s population and caused significant budget shortfalls. As a result, Appalachia implemented interventions such as establishing alternative industries, supporting economic diversification and infrastructure development in the region to cushion the impacts of these challenges. This strategy can be replicated in the affected communities in Nigeria to ensure a smooth transition process. In addition, it is essential to properly engage affected communities to develop transition strategies and ensure they are equitable and responsive to community needs.

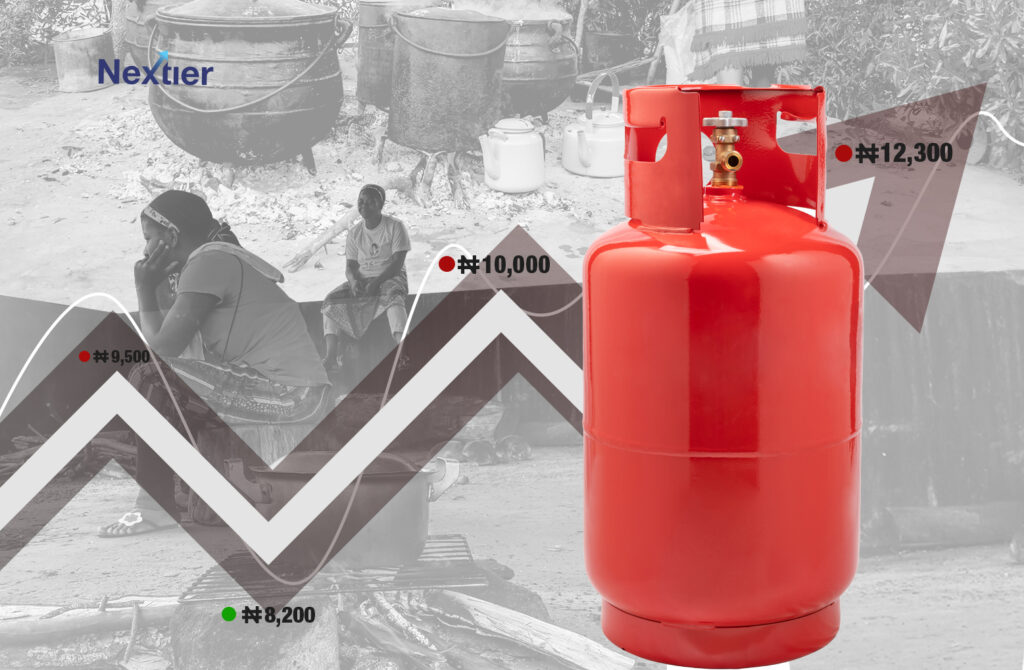

Another social challenge that can impede the actualisation of the ETP is the lack of sensitisation and awareness creation. 175 million people in Nigeria (87% of the population) lack access to clean cooking, resulting in significant quantity and length of life repercussions for mainly women and children. The ETP proposes to bring modern cooking alternatives to the general population through a decarbonisation strategy of moving from traditional firewood, charcoal and kerosene to liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), electric cookstoves and biogas. However, there is still a significant gap in awareness and sensitisation about the need to move to cleaner alternatives. To foster wider acceptance and adoption of cleaner cooking sources, intentional education and awareness campaigns targeted towards the population, particularly in the rural communities, are required to prevent potential anxiety around sub-optimal benefits of using LPG, electric cookstoves and biogas.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s ETP is a bold and ambitious plan with the potential to transform the country’s energy sector and economy. The effective execution of the plan hinges on taking into account the social and environmental repercussions, and mitigation strategies like public awareness, adequate funding, and policy coherence must be employed to address the potential negative impact and ensure a just and sustainable energy transition.